The Intellectual Property Office of Singapore rejected the Ex parte hearing of Trademark application for the slogan “PARTY LIKE GATSBY” as the slogans are a category of marks for which it is often more difficult to establish distinctiveness than it is for others. The slogans often suffer from a disability from a trade mark point of view since they are usually laudatory about some aspect or quality of the goods or services in question.

FACTS OF THE CASE

The Arangur UG (haftungsbeschränkt) (the “Applicant”) filed a Trademark application to register the Trademark “PARTY LIKE GATSBY” under classes 41 and 43. the examiner examining the Subject Application issued the first office action objecting to the Application Mark under Section 7(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1998 (the “Act”), The examiner determined that the Application Mark devoid of any distinctive character. The Application Mark, which consists of the statement “PARTY LIKE GATSBY,” serves as a promotional statement implying that the services filed for allow their consumers to host or be a part of a party like Gatsby from the book and film “The Great Gatsby.”

As a result, in the absence of an accompanying house mark or other elements that would confer distinctiveness, such as a high degree of stylisation, the examiner concluded that the mark is unlikely to be perceived as a badge of origin without prior education of the average consumer. To overcome the Section 7(1)(b) objection, the examiner invited the Applicant to file evidence of use.

First, the Applicant submits that the examiner erred in finding that the Application Mark serves as “a promotional statement suggesting that the services filed for allow its consumers to host or be part of a party like Gatsby from the book and movie ‘The Great Gatsby’”. Second, although the name “Gatsby” is associated with lavish parties, the Applicant contends that the entire slogan “Party Like Gatsby” is sufficiently distinctive because it is not promotional or laudatory. The Application Mark is not particularly imaginative, but it does have a certain originality that consumers are likely to remember. Lastly, the meaning and originality of the Application Mark will be perceived as an inducement to purchase, but it is not merely informational. The Applicant contends that there is no evidence that consumers would immediately associate the novel “The Great Gatsby” or the character of Jay Gatsby with the remaining services, and that the relevant public will be required to place the Application Mark in a specific context, which will necessitate intellectual effort.

JUDGMENT

The necessary element for the trademark to get registration is the distinctiveness in the sense of indicating the origin of goods or services bearing the mark. Under the act, requirement of distinctiveness finds expression in, Section 7(1)(b). The applicant has not amassed sufficient evidence of use of the Application Mark to support a claim that the Application Mark has acquired distinctiveness as a result of its use in Singapore. the fact that a slogan is able to trigger a cognitive process in the minds of the relevant public was not the sole or decisive basis for the finding of distinctive character. When viewed as a whole, the IP Adjudicator do not consider that the Application Mark is inherently distinctive as an indication of trade origin so as to overcome the objection under Section 7(1)(b) of the Act. Hence, the present case turns entirely on the lack of distinctiveness of the Application Mark.

KS&CO COMMENT

Brand taglines are catch phrases which serve to draw a connection for consumers with business products and services. While slogans can be useful in advertising and promotion, attempts to register them as registered trademarks are frequently unsuccessful due to a lack of evidence of their use in the marketplace. Slogans are frequently composed of ordinary words and phrases that are laudatory or calls to action, making it difficult for them to satisfy the basic requirement of distinctiveness as an indication of trade origin that is required for trade mark registration.

In the copyright infringement case between Ed Sheeran and Sami Chokri, The UK High court ruled in favour of Ed Sheeran’s 2017 hit “Shape of you” that the star did not copy and infringed the 2015 song called “Oh Why” realeassed by Sami Chokri, who performs as Sami Switch, and music producer Ross O’Donoghue.

Sami Chokri claimed in 2017 that Ed Sheeran copied his “Oh Why” hook with the similar “Oh I” in Sheeran’s UK best-selling song “Shape of You.” Chokri claimed that Sheeran had previously heard his song and had purposefully copied the notes. Sheeran took a stand and filed a lawsuit against Chokri, seeking a declaration that he did not violate Chokri’s copyright, to which Chokri counterclaimed and restated his original claim. Sheeran claimed “differences between the relevant parts” of the songs “provide compelling evidence that the ‘Oh I’ phrase” in Sheeran’s song “originated from sources other than Oh Why.”

On April 6, Judge Antony Zacaroli ruled that Sheeran had “neither intentionally nor unintentionally copied” Chokri’s song. He admitted that “similarities between the one-bar phrase” in Shape of You and “Oh Why” existed, but that “such similarities are only a starting point for a possible infringement” of copyright. To demonstrate that the similarities are not merely coincidental, he asked Chokri to provide proof that Sheeran had heard his song prior to its release. But Chokri’s team failed to prove that Oh why had ever graced the Ed sheeran’s speakers. After which Ed Sheeran made a statement in the social media account that lawsuits are “baseless” and are not pleasant experience which is damaging the music industry.

The judge also stated that the two phrases at issue “play very different roles in their respective songs,” with the “Oh Why” hook reflecting the song’s “slow, brooding, and questioning mood” and Sheeran’s “Oh I” line acting as “something catchy to fill the bar.” In the most basic sense, the hook is unmistakably similar. The melodic formation and rhythmic clicking appear similar, as does the melodic progression, according to forensic musicologists on Chokri’s side. But Sheeran and some musicologists have also called the similar-sounding hook “entirely commonplace” because the melodic structure was extremely common.

KS&CO COMMENT

Copyright is supposed to encourage the artistic endeavour. The outcome of this case restores the balance, protecting only original expressions of creativity. It should relieve the songwriters. The law must strike an appropriate balance between safeguarding and encouraging creativity because it becomes difficult to prove that the artists have never heard the song before.

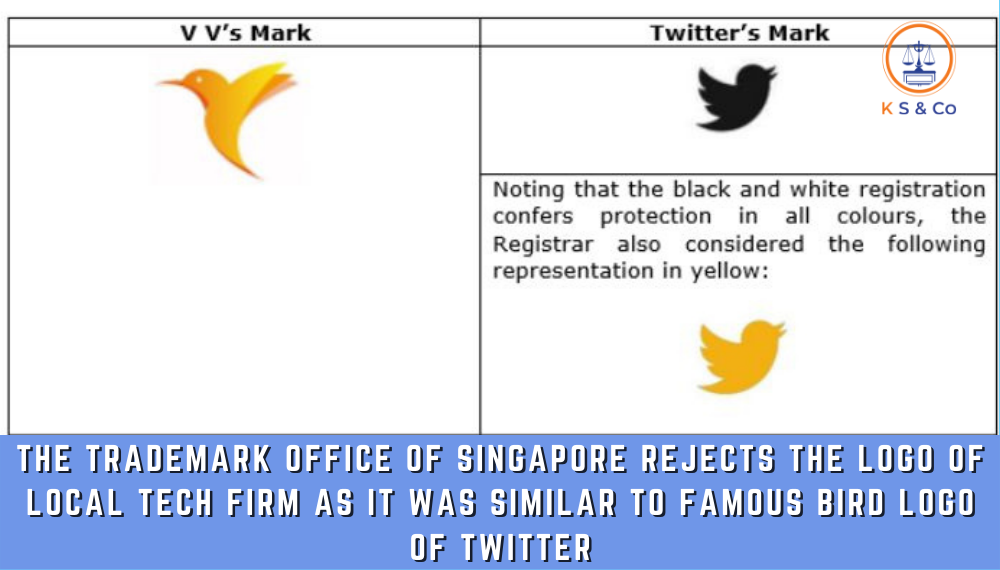

On 10th September 2018, a Singaporean firm VV Technology Pte. Ltd (Applicant) applied to register the logo of flying bird, with an eye, pictured from its side in class 42. They planned to use the trademark for a mobile application for online shopping and food delivery services. The twitter, Inc (Opponent), American social media giant filed for the opposition of the trademark on 24th September, 2019 citing the similarities of the logo to its well known trademark between the two.

According to the Applicant, the Application Mark contains a pictorial representation of the Applicant’s initials, ‘VV’, and depicts a hummingbird. They also claimed that the consumers of mobile user app are “digital native” who would not be confused by the two similar-looking bird logos. The reputation of the Twitter logo reduces the likelihood that the public will be confused by the two marks because the global reputation of Twitter will be little affected by a small start-up company, and thus consumers are unlikely to confuse them. Twitter submitted that the marks are aurally identical as consumers would refer to both as “bird marks”. Twitter submitted that both marks evoke the idea of a flying bird, which outweighs any visual or aural differences.

ISSUES –

- Whether the Application Mark is similar to the earlier Opponent’s Mark?

- Whether the Application mark has infringed the Opponent’s Mark?

DECISION-

The Opponent filed for the grounds of opposition under section 8(2)(b) and 8(7)(b) of the act to which the registrar noted that the Application Mark is visually similar, aural similar and conceptually similar to the Opponent’s Marks. The Registrar rejected VV Technology’s arguments regarding the parties’ goods and services’ for various commercial uses. He stressed that the degree of similarity is determined by comparing the specifications under the respective marks rather than how they are used or intended to be used. Using this method, he discovered that the goods and services directly overlapped.

According to the Registrar, consumers are more likely to perceive an economic link between the two marks that the Application Mark is either a new iteration of the Opponent’s Mark, or that the Application Mark is a modified mark that the Opponent is using for new closely related digital services that are extensions of the Opponent’s existing range of services. As the opponent has built up goodwill in its Singapore operations, it may be intended that the Opponent established this element after determining that there is a likelihood of confusion and that the Applicant’s misrepresentation poses a real risk of diverting sales and custom away from the Opponent which would amount to passing off. Thus after considering all the evidences and pleadings, the registrar rejected the trademark application of the applicant’s logo and twitter succeeded in the opposition.

KS&CO COMMENT

This case raises a complex matter regarding the similarity between the two device marks and likelihood of confusion arising in the minds of the consumers in a digital world. When evaluating device marks, a simple approach is required. This is especially true for simple stylisations like device marks used as icons in mobile apps and user interfaces. This decision provides a useful overview of the principles that apply when dealing with such marks.

The full bench of the Federal Court of Australia overturned the ruling of Thaler v. Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCA 879 which stated that AI can be treated as inventor. Artificial intelligence systems are built into machines and are engineered to mimic specific human cognitive processes and activities. Artificial neural networks are computer programmes that self-organize to stimulate the way the human brain analyses and creates information. Artificial intelligence networks may be used in or make up artificial intelligence systems.

FACTS

The case involved the AI system DABUS (Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience) and patent applicant Dr. Stephen L. Thaler. The Patent Cooperation Treaty application was filed in 2019 by Professor Ryan Abbott of the University of Surrey, with Dr. Thaler as the applicant and DABUS as the inventor. Thaler, an expert in applied and theoretical artificial neural network technology, owns the source code for DABUS as well as the computer that runs it. He also uses DABUS with the PC. Various items and techniques for an enhanced fractal container were mentioned in the patent application. According to Abbott, the AI system was in charge of a large portion of the labour that went into creating the inventions on its own.

The Patent Office rejected DABUS as the inventor since the AI system was not a natural person. However, Australia’s Federal Court ruled that AI may indeed be named as inventor. The Commissioner of Patents appealed this decision to the Full bench of the Federal Court.

ISSUES

Whether a device characterized as an artificial intelligence machine can be considered to be an “inventor” within the meaning ascribed to that term in the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) and the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth).

JUDGEMENT

The appeal was approved by the Full Federal Court of Australia, which overturned the judgment of the first instance. The court held that only a natural person can be an inventor for the purposes of the Patents Act and Regulations, taking into account the statutory language, structure, and history of the Patents Act, as well as the policy objectives underlying the legislative scheme. Furthermore, for someone to be eligible for a patent such an inventor must be named under ss 15(1)(b)-(d). It followed that naming DABUS as the inventor meant the application had lapsed and Dr Thaler could not be entitled to be granted the patent.

The Full Court used a traditional approach to statutory interpretation in reaching this conclusion, considering the use of the term “inventor” in these and other provisions of the Patents Act, the explanatory material, previous iterations of the legislation, and case law involving the inventor’s role. The Full Court determined that the logical reading of these clauses was that an ‘inventor’ must be a natural person, i.e., a person from whom another person can get a patent u/s 15(1) (b)-(d). The Patents Act’s structure and the history of patent law evolution supported this interpretation.

Accordingly, the Full Court held that only a natural person can be an inventor for the purposes of the Patents Act and Regulations.

KS&CO COMMENT

The European Patent Office board concluded last year that AI systems cannot be cited as an inventor on a patent application because a European patent application must have a designated inventor who has legal ability. As a result, AI systems lack an identity, a name, an address, or a nationality, and they are unable to provide evidence, so mentioning an AI system on a patent application is virtually worthless.