Introduction

In arbitration, the principle of minimal judicial intervention serves as a cornerstone, underscoring the autonomy and efficiency of arbitral tribunals in resolving disputes. However, courts are endowed with specific powers to ensure the arbitral process remains within the bounds of law, fairness, and public policy. These powers often manifest in critical junctures such as appointing arbitrators, granting interim reliefs, or addressing challenges to awards. This month’s Newsletter is in two parts:- Part I will discuss recent developments in arbitration, focusing on the ongoing balance between judicial authority and arbitral independence and Part II will discuss the recent development focusing on the Draft Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024 which aims to enhance and streamline India’s arbitration framework by formalizing procedures, reduce judicial intervention, and enhance institutional arbitration, further shaping India’s arbitration landscape in line with global standards.

PART-I

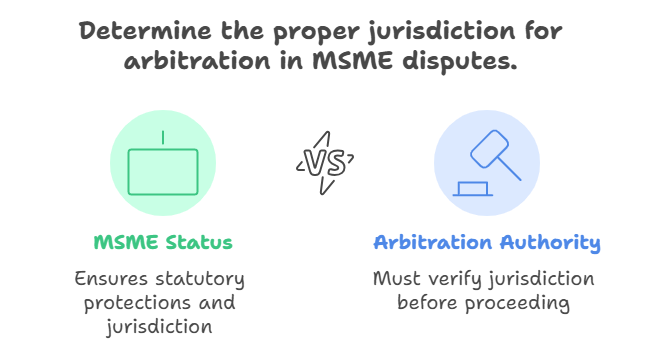

The intersection of MSME status and arbitration raises critical issues of jurisdiction and authority. This case highlights the limits of an arbitrator’s role, emphasizing that once an MSME’s status is disputed, the arbitrator cannot proceed to decide the merits of the case without first addressing the statutory requirements under the MSMED Act.

Sivadharshini papers Ltd vs Sunwin Papers Ltd.

Citation: O.S.A.(Comm.App.Div.) No.7 of 2023 and C.M.P.No.2407 of 2023 and C.M.P.No.16053 of 2024

Date of the Judgment: 30.10.2024

Court: Madras High Court

Ruling: The arbitrator cannot decide a case on merits after concluding that the supplier is not an MSME.

Facts:

The case involves a dispute between M/s. Sivadarshini Papers Limited (appellant) and M/s. Sunwin Papers (respondent). The respondent supplied waste paper to the appellant but alleged that the appellant failed to make payments for these supplies. The respondent was registered as an MSME on November 9, 2016, under the MSMED Act, 2006, and approached the Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation Council (MSEFC) in Madurai for redressal. Conciliation attempts failed, and the dispute was referred to arbitration under Section 18(3) of the MSMED Act. The appellant contended that the respondent was not a valid MSME at the time of the transaction or when referred to arbitration, and that no payments were due. The Sole Arbitrator held that the respondent was not a valid MSME based on an Office Memorandum dated June 27, 2017, but proceeded to rule on the merits of the dispute, concluding that no dues were payable by the appellant. Aggrieved, the respondent filed a petition under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, challenging the arbitral award.

Issue:

- Whether the court has the power to adjudicate upon jurisdiction of the Arbitration tribunal under Section 34 of the act or is it the Tribunal’s jurisdiction to decide upon its own jurisdiction?

- If there can be a reference to arbitration in a case where the appellant was claimed to be excluded as an MSME as per 2017 notification?

Judgment:

The High Court dismissed the appeal filed by M/s. Sivadarshini Papers Limited. The court upheld the setting aside of the arbitration award and directed the case to be referred to a new Arbitrator for fresh adjudication. The registry was instructed to nominate a new Arbitrator through the High Court’s Mediation and Conciliation Centre. The appeal was dismissed without costs, and all connected miscellaneous petitions were closed. The Commercial Court set aside the arbitral award, confirming the respondent’s MSME status based on valid Udyog Aadhaar certifications and ruling that the Sole Arbitrator erred in addressing merits after rejecting the MSME registration. It held the award to be patently illegal and in conflict with public policy under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act. The court also emphasized that the Arbitrator should not have proceeded on merits after ruling on the registration issue.

K S & Co Comments:

The decision in Sivadarshini Papers Ltd. v. Sunwin Papers Ltd. is a significant development in the evolving legal landscape surrounding the MSMED Act, 2006, and the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. This judgment reinforces the judiciary’s commitment to safeguarding the statutory protections granted to MSMEs, a vital component of India’s economic growth strategy. MSME’s have been provided with statutory protection to ensure that small businesses and organizations’ economic interest are protected from companies with huge capital and largely funded industries. The impugned award was set aside by the Hon’ble court on the rationale that an award dealing with merits of case cannot be decided where the jurisdiction of the tribunal is contested. By balancing equity and procedural integrity, the judgment not only upholds justice for MSMEs but also enhances trust in India’s legal and commercial systems, setting a precedent that will influence future disputes involving MSMEs and arbitration.

When arbitration intersects with disputes rooted in statutory mandates, courts often step in to delineate boundaries. This case underscores that disputes involving the governance of public charitable trusts, which affect broader public interest, must adhere to the procedural safeguards of Section 92 of Civil Procedure Code, beyond the scope of arbitration.

Sanjit Singh Salwan And 4 Others v. Sardar Inderjit Singh Salwan And 2 Others

Case Number: Appeal under section 37 of Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996- No. 356 of 2024

Date of the Judgment: 30.08.2024

Court: Allahabad High Court

Ruling: Dispute relating to members and management of Public Trusts are not arbitrable, must file Suit U/S 92 CPC

Facts:

In this case the management of Guru Tegh Bahadur Public School in Meerut, operated by the Guru Tegh Bahadur Charitable Trust. Both the appellants and respondents claim to be trustees. After a suit for injunction filed by the respondents was dismissed, the parties agreed to arbitration, resulting in an arbitral award on 30.12.2022. The appellants complied with the award, but the respondents later filed an application with the arbitrator, leading to an ex-parte award on 30.10.2023. The appellants claimed they were unaware of this second award until objections were filed in subsequent proceedings. The appellants sought execution of the 2022 award but later withdrew the execution case. They then filed a Section 9 application before the Commercial Court, Meerut, seeking to prevent the respondents from interfering with the school and trust’s management. Meanwhile, the respondents obtained an order from the arbitrator on 21.01.2024, restraining the appellants from interfering in the school’s operations. The appellants challenged the 30.10.2023 award under Section 34 of the Arbitration Act and the 21.01.2024 order under Section 37. The Commercial Court ruled that trust disputes are not arbitrable, declaring both awards null and void, and rejected the Section 9 application. The appellants subsequently appealed against the Commercial Court’s decision.

Issues:

Whether a dispute involving a charitable trust is arbitrable?

Judgment:

The court held that disputes concerning the Guru Tegh Bahadur Charitable Trust, a public trust, were non-arbitrable under Section 92 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC). Section 92 mandates that matters such as removal or appointment of trustees, property vesting, and trust management, involving charitable or religious trusts, must be adjudicated through the specific procedure prescribed therein. The court observed that the arbitral awards addressed issues like trustee removal, induction, and operational management, which fall squarely within the scope of Section 92 and are thus beyond the purview of arbitration. Additionally, the court noted that disputes following the lodging of an FIR were also non-arbitrable, as investigations were already underway. Citing Section 92(2), the court emphasized that such matters must be adjudicated by courts, not arbitrators, and upheld the Commercial Court’s ruling that the arbitral awards were null and void. The court emphasized that disputes related to public charitable trusts are explicitly covered under Section 92 of the CPC, which lays out a distinct process for such matters to reaffirm that disputes concerning public trusts are non-arbitrable because they deal with public interest and governance rather than contractual or private rights between individuals.

K S & Co Comments:

The judgment in Sanjit Singh Salwan & Ors. v. Sardar Inderjit Singh Salwan & Ors. serves as a critical precedent in reaffirming the non-arbitrability of disputes involving public charitable trusts especially when there is a statutory provision barring the same. The Allahabad High Court emphasized that such disputes, governed by Section 92 of the Code of Civil Procedure, address issues of public interest, including the removal or appointment of trustees and management of trust property, which require judicial oversight rather than private arbitration. This ruling is significant as it delineates the boundaries of arbitration, ensuring that matters involving public governance and statutory compliance are adjudicated within the appropriate judicial framework. By reinforcing the sanctity of Section 92 CPC, the judgment safeguards the integrity of public trusts and underscores the judiciary’s role in protecting public interest, providing clarity on the limitations of arbitration in disputes transcending private contractual rights.

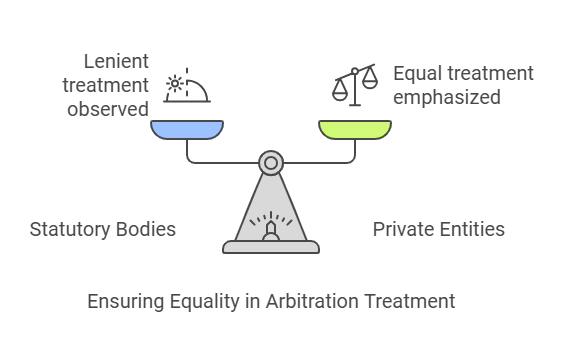

The enforcement of arbitral awards in disputes involving statutory bodies raises critical questions about the application of Section 36 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act. Recently the Hon’ble Supreme Court highlighted the need for consistent treatment of both private and government parties in arbitration, emphasizing that the status of the respondent as a statutory body cannot be used to impose different conditions for the stay of execution.

International Seaport Dredging Pvt. Ltd. v. Kamaraja Port Limited

Citation: 2024 SCC OnLine SC 3112.

Date of judgement: 24.10.2024

Court: Hon’ble Supreme Court.

Ruling: The provisions of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 cannot be applied differently in regard to the status of the respondent as a statutory undertaking/ government authority.

Facts:

The respondent awarded a contract worth Rs. 274 crores to the appellant for executing Capital Dredging Phase-III at Kamarajar Port, with a completion deadline of 11.04.2017. Disputes arose during the project, prompting the appellant to invoke the arbitration clause. In its final award on 07.03.2024, the arbitral tribunal directed the respondent to pay the appellant Rs. 21,07,66,621 for the claims allowed, along with interest (9% per annum from 15.11.2017, escalating to 12% if delayed) and costs of Rs. 3,20,86,405. Post-award, the parties filed applications for clarifications. The tribunal dismissed the respondent’s application but partially allowed the appellant’s, increasing costs by Rs. 12,00,000. The respondent challenged the award under Section 34 of the Arbitration Act, seeking a stay on its execution. On 09.09.2024, the High Court granted a stay, conditional upon the respondent providing a bank guarantee for Rs. 21,07,66,621 within eight weeks.

Issue:

- Whether the High Court was justified in directing the Respondent to furnish only a bank guarantee rather than deposit the awarded amount as a condition for stay?

- Whether the Respondent’s status as a statutory body could be considered in determining the conditions for granting a stay?

Judgment:

The Supreme Court reviewed the case in the context of Section 36 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, which governs the enforceability of arbitral awards. It clarified that under Section 36(2), an arbitral award is not automatically unenforceable simply because a challenge is filed under Section 34. Instead, a stay on execution can be granted under Section 36(3), but the court must impose appropriate conditions for such a stay. The Court found that the High Court had incorrectly relied on the respondent’s status as a statutory body to justify the requirement for a bank guarantee, as well as the exclusion of interest and costs from the stay conditions. The Supreme Court emphasized that arbitration proceedings are based on the principle of equality under Section 18 of the Arbitration Act, which treats both government bodies and private parties the same. Therefore, the High Court’s reliance on subjective factors, such as the respondent’s status, was misplaced.

Additionally, the Supreme Court pointed out that the High Court had focused on just one aspect of the arbitral award—related to a claim for a refund under the Building and Other Construction Workers’ Welfare Cess Act, 1996—while neglecting other claims totaling around ₹18 crores. This selective approach undermined the arbitral tribunal’s decision and failed to account for the full scope of the award.

K S& Co Comments:

It has usually been observed that in cases where government bodies or Public Service Undertaking are involved, the court has taken a lenient approach towards them. However, in this judgment the Hon’ble Supreme Court has taken a positively contrasting stand by reinforces the principle of equality in arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, by emphasizing that government entities and statutory bodies cannot be treated differently from private parties. It clarifies that stays on arbitral awards under Section 36(3) must be based on objective criteria, rejecting the High Court’s reliance on the respondent’s statutory status to impose lenient conditions. This pro-arbitration judgment ensures that arbitral awards are treated with equal enforceability, fostering confidence in arbitration as a neutral dispute resolution mechanism. By discouraging selective interpretations of awards, the decision upholds the integrity of the arbitral process and highlights that public sector entities cannot seek preferential treatment solely due to their statutory nature, thereby promoting fairness and consistency in arbitration law.

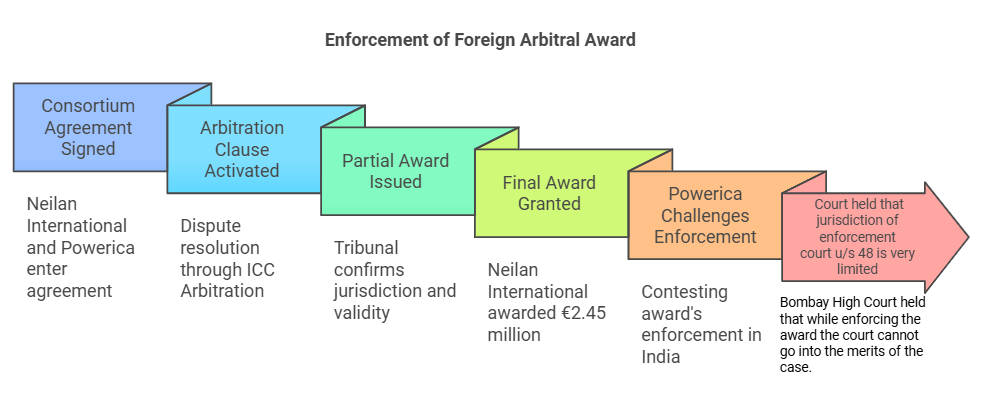

In the context of enforcing foreign arbitral awards, courts are constrained by limited grounds for intervention under Section 48 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act. This case reinforces the principle that, while a foreign award may be challenged on public policy grounds, the court cannot review the merits of the dispute or the tribunal’s findings in the enforcement process.

Neilan International Co Limited Vs. Powerica Limited

Citation: MANU/MH/7103/2024

Date of judgement: 27.11.2024

Court: Bombay High Court

Ruling: Court Cannot Go Into Merits While Enforcing Foreign Award U/S 48 Of Arbitration Act:

Facts:

The case between Neilan International Co. Limited and Powerica Limited revolves around an arbitration dispute stemming from a Consortium Agreement signed on January 30, 2006, for the construction of power plants in Sudan. The agreement established that any disputes would be resolved through arbitration under the ICC Arbitration Rules, with proceedings taking place in London. Following the execution of two contracts on May 9, 2006, between Powerica and the National Electricity Corporation of Sudan (NEC), which governed the design and construction of thermal power plants, NEC assigned certain rights to Neilan International in December 2007. Subsequently, a Deed of Assignment was executed on December 24, 2012, transferring a debt of Euro 2.7 million from STGP to Neilan International due to breaches of contract. Arbitration proceedings commenced, during which Powerica raised a preliminary issue regarding the existence of a binding arbitration agreement. The tribunal ultimately issued a Partial Award on April 21, 2015, confirming jurisdiction and the validity of the arbitration agreement. A Final Award followed on September 27, 2018, awarding Neilan International Euro 2.45 million. Powerica did not challenge these awards in London but later contested the Final Award’s enforcement in India, arguing it violated public policy due to the unilateral nature of the assignment and lack of consent from Powerica.

Issues:

Whether an enforcement court has the jurisdiction to go into merits of the award while enforcing the said foreign award?

Judgment:

The court upheld the Final Award dated September 27, 2018, which had awarded Neilan International Euro 2.45 million and costs. The court found that a binding arbitration agreement existed between the parties, as determined by the tribunal in its Partial Award issued on April 21, 2015, which had not been challenged by Powerica in London. The court emphasized that enforcement of foreign arbitral awards could only be resisted on limited grounds, primarily concerning public policy. Although Powerica argued that the assignment of contracts to Neilan International was invalid due to lack of consent and contrary to Indian public policy, the court ruled that these arguments did not suffice to deny enforcement. It reasoned that the tribunal’s findings regarding the validity of the assignment under Sudanese law were binding and that both India and the UK are signatories to the New York Convention, reinforcing the enforceability of such awards. Ultimately, the court dismissed Powerica’s objections and ordered the enforcement of the Final Award, affirming that it did not contravene Indian public policy or fundamental principles of justice. This ruling underscored the importance of respecting international arbitration agreements and awards while limiting judicial intervention in their enforcement based on public policy considerations.

While enforcing foreign awards under Section 48 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act,1996 courts cannot go into the merits of the case as jurisdiction of the enforcement court under this section is very limited. The judge also held that jurisdiction of the enforcement court under section 48 of the Arbitration is very limited and while enforcing the award the court cannot go into the merits of the case.

K S& Co Comments:

This case is pivotal in reinforcing the principles of international arbitration and the enforcement of arbitral awards in India. The court ruled that enforcement of foreign arbitral awards can only be resisted on very limited grounds, primarily concerning public policy, and found that Powerica’s objections regarding the validity of contract assignments and lack of consent did not suffice to deny enforcement. This decision not only strengthens India’s pro-arbitration stance but also highlights the importance of clarity in arbitration agreements and assignments, serving as a critical reference for future cross-border commercial disputes.