Trademark squatting refers to the deliberate registration of another entity’s trademark, typically in jurisdictions where the original mark is not yet protected. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) defines it as “the registration or use of a generally well-known foreign trademark that is not registered in the country or is invalid as a result of non-use”. Unlike legitimate trademark registration, squatting involves securing trademark rights without genuine intent to use the mark in commerce, but rather to extract profit through various means.

WHY THIS MATERS NOW

When Apple paid US $60 million in 2012 to reclaim the word “iPad” in China, boardrooms worldwide woke up to trademark squatting—the practice of registering someone else’s brand first and later selling or blocking it. In this case, Apple’s dispute with Shenzhen Proview Technology was about who owned the “iPad” trademark in China. Proview had registered the name in China years before Apple launched its iPad.

Apple bought the rights from Proview’s Taiwanese branch in 2009, but Proview’s Chinese subsidiary said that deal didn’t cover China. This led to legal battles where Proview tried to stop Apple from selling iPads in China. In 2012, Apple settled by paying $60 million to Proview, securing the trademark rights and allowing iPads to be sold freely in China. This case shows how trademark squatting can cause big problems even for large companies.[1]

Thirteen years later, the same playbook is unfolding across India’s tier‑2 cities. Rising purchasing power in places like Pune, Indore, and Coimbatore has turned them into magnets for both legitimate expansion and opportunistic filings.

BURGER KING CORPORATION V. ANAHITA & SHAPOOR IRANI[2]

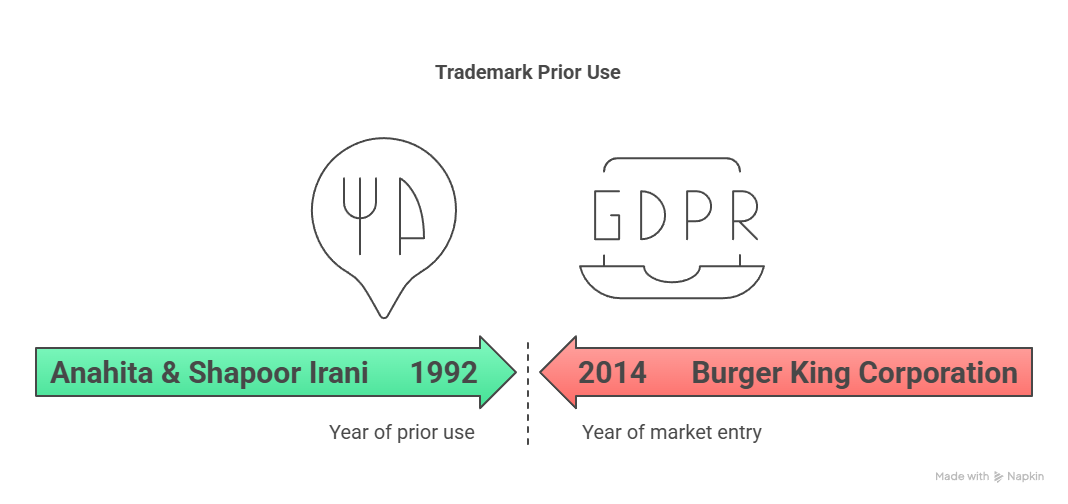

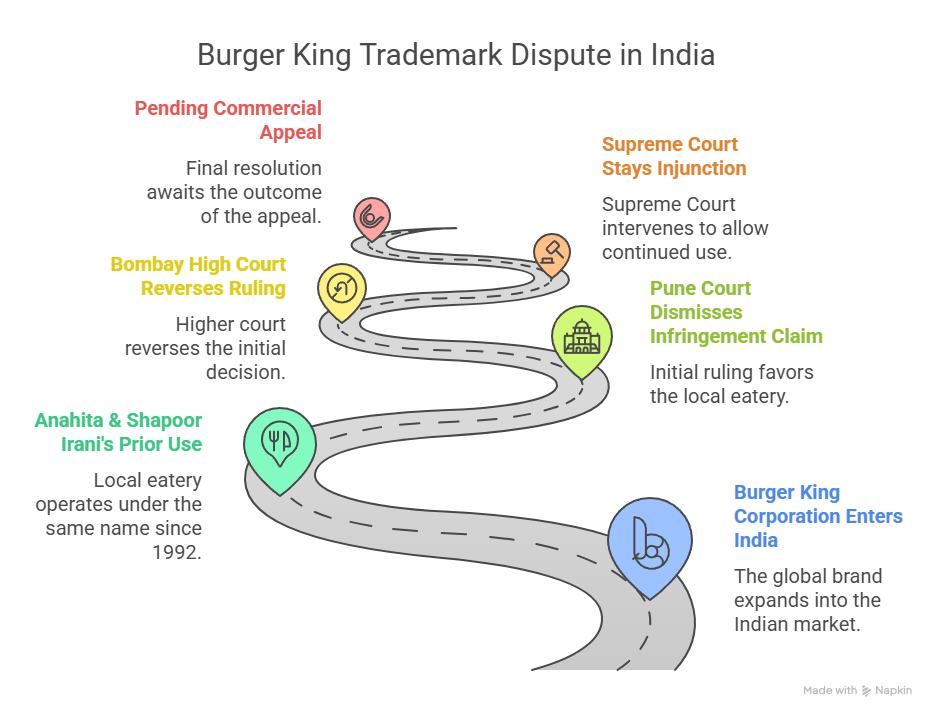

The Burger King Corporation v. Anahita & Shapoor Irani case is a significant example of how Indian trademark law tends to favor prior local use over the global reputation of a brand. The legal journey began in August 2024, when a Pune court ruled in favor of the Iranis—owners of a small eatery that has been operating under the name “Burger King” since 1992. The court dismissed the trademark infringement claims brought by the American fast-food giant, which officially entered the Indian market much later, in 2014.

However, this decision was overturned in December 2024 by the Bombay High Court, which issued an injunction preventing the Iranis from using the name “Burger King.” This created a major turning point in the case and raised concerns about the treatment of long-standing local businesses when confronted by powerful global brands.

In March 2025, the Supreme Court of India temporarily stayed the High Court’s order, allowing the Iranis to continue operating under the name for now, while the case awaits final resolution. This move signals the Supreme Court’s recognition of territorial rights and genuine prior use, suggesting that even well-known international companies must act promptly to protect their trademarks in foreign markets.

The ongoing commercial appeal in the Bombay High Court is expected to clarify how India balances the rights of local businesses with registered trademarks versus prior use, especially in cases of trademark squatting—where individuals register popular foreign brand names in countries where those brands haven’t yet established legal rights.

For businesses, the case serves as a strong reminder: register your trademarks early in any market you plan to enter, or risk losing control of your brand to opportunistic claimants.

SQUATTING, PRIOR USE AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN

| Type of risk | Explanation | Illustrative cases |

| Classic Squatting

(bad‑faith first‑to‑file)

|

“First to file” beats “first to use” (but many countries gives significant weight t actual use) | Proview registered the “iPad” trademark in China long before Apple entered the market, and then challenged Apple’s rights, forcing Apple to pay $60 million to secure the trademark. This shows how squatters exploit the first-to-file system by registering trademarks without intent to use them legitimately, causing costly disputes for brand owners trying to expand internationally. |

| Market -Obstruction

|

Filing identical mark to block entry | Starbucks encountered delay entering the Russian market due to trademark squatting. The company was forced into legal proceedings against a Russian national who had preemptively registered the Starbucks trademark in Russia. This case illustrates how squatting can serve as a strategic barrier to market entry. |

| Hoarding / Mass Trafficking | Bulk registration of famous marks across classes | In a significant Indian case, Hengst SE & Anr. v. Tejmeet Singh Sethi & Anr[3]., the Delhi High Court took action against defendants found to be squatting on 378 well-known marks belonging to various entities. The court ordered the defendants to withdraw all applications infringing on well-known marks, demonstrating judicial recognition of the systematic nature of trademark squatting operations. |

| Prior-Use Collision | Earlier honest use in one district beats later national registration | The global Burger King chain faced a legal hurdle in India when a local Pune restaurant, using the “Burger King” name since 1992, asserted its right to the mark before the multinational’s 2014 entry. The dispute highlights how trademark squatting—or the risk of it—can block international brands from using their own names in new markets if local parties have already registered or used the mark, intentionally or otherwise[4]

|

| Digital Squatting | Domains / app names / social handles | Countless .in and .co domains resold to MNCs. Some of the examples are:

Amazon-india.online: A domain mimicking Amazon, specifically targeting Indian users to steal credentials through phishing Growtiktok.com, Tktokcharts.com, Tiktokexposure.com, Tiktokplant.com: Domains registered to capitalize on TikTok’s brand |

WHY TIER‑2 CITIES ARE FERTILE GROUND

- Metro‑first roll‑outs leave years‑long gaps before brands reach secondary cities.

- Lower IP policing; local registrars and entrepreneurs may never have seen the international mark.

- Language diversity creates more variants to grab (Hindi, Marathi, Tamil transliterations).

- Rapid consumer growth makes each hijacked mark genuinely valuable.

WHAT THE SONY PS5 AND XIAOMI STORIES ADD

- Sony’s launch of PlayStation 5 in India was delayed because a squatter had filed a trademark application for “PS5” covering identical specifications to Sony’s existing PS4 registration. Although the application was eventually withdrawn following opposition proceedings, the damage in terms of market delay had already occurred.

- Chinese electronics company Xiaomi and an individual named Chen Xiong. In July 2017, Xiaomi introduced a smart speaker featuring a voice-activated command prompt called “小爱同学” (Xiao Ai Tong Xue). Just one month later, Chen registered this name as a trademark and subsequently expanded his portfolio to 66 marks across 21 different classes.

After securing registration, Chen demanded Xiaomi cease using the name and began applying the trademark to his own products to establish legitimate use. Xiaomi filed a lawsuit arguing unfair competition and trademark squatting. In December 2023, the Wenzhou Court ruled in Xiaomi’s favor, acknowledging that the name had become associated with Xiaomi’s products and had gained considerable market recognition.

A SEVEN‑STEP DEFENSE GAME‑PLAN

- Map the Expansion Roadmap

Begin by identifying every state and Tier-2 city included in your three-year growth plan. This territorial map will guide your trademark filings and highlight areas where your brand might otherwise be vulnerable. Too often, businesses secure rights in major metros but overlook smaller cities — a gap that opportunistic players can exploit by registering or using your brand in those unprotected markets.

- File Early — Across All Relevant Classes

Trademark protection isn’t just about your current offering. File registrations in all relevant classes — not only those covering your present products or services but also those aligned with future spin-offs or adjacent categories. For example, a food delivery brand may eventually enter packaged foods, cloud kitchens, or even merchandising — each requiring protection in different classes. Broad and early coverage deters squatters who thrive on class-specific gaps.

- Secure Variants, Scripts & Hashtags

In a multilingual country like India, brand risk multiplies with language. Register regional script versions of your brand name — Hindi, Tamil, Bengali, and others — along with common misspellings, abbreviations, and phonetic variants. Do not ignore the digital layer: hashtags, social media handles, and domain names should also be secured. This ensures consistency across markets and platforms, and makes it harder for imitators to pass off or confuse consumers.

- Use the Madrid Protocol for Global Reach

If your business has global aspirations, streamline your international trademark filings through the Madrid Protocol. This treaty allows you to file a single application via India’s IP office and extend coverage to over 130 countries. It significantly reduces administrative burden and legal costs while ensuring your brand is protected as you scale abroad.

- Monitor Filings & Oppose Fast

Set up alerts or use a trademark watch service to monitor new applications that resemble your brand. If a conflicting mark is filed, act swiftly during the advertised stage by filing an opposition. This pre-grant intervention is far more efficient and cost-effective than trying to cancel a registered mark later through litigation.

- Document Genuine Use

Maintain a systematic archive of dated brand use in each market — ads, invoices, website captures, packaging, and social posts. These records act as critical proof in case your trademark rights are challenged or if you need to establish prior use in a legal dispute. Being able to show genuine use can make the difference between winning or losing an opposition or enforcement action.

- Be Litigation-Ready

Identify local counsel, budgets, and preferred fora before trouble hits. Days saved early ≈ crores saved later.

IF YOU DISCOVER A SQUATTER

- Oppose or cancel the mark citing bad faith / non‑

- Negotiate quietly with the squatter—sometimes paying a modest buy-back fee is faster and cheaper than a lengthy lawsuit.

- Well-known status in India gives your brand broader legal protection—even against local users. It is a smart move for widely recognized brands.

- Leverage prior‑use doctrine if you can prove earlier honest use in the country.

POLICY OUTLOOK

Indian courts are ready to punish systematic hoarding. Draft amendments to the Trade Marks Rules now under consultation aim to tighten bad‑faith examinations and introduce faster show‑use requirements. If adopted, they could further shrink the squatter’s window.

K SINGHANIA & CO VIEWS:

Trademark squatting is no longer a fringe nuisance. In India’s tier‑2 cities it is becoming a competitive weapon—sometimes wielded by opportunists, sometimes by genuine earlier adopters. Either way, the cost of filing early is a fraction of the cost of fighting late.

The authors Ms. Srishti Singhania and Ms. Shikha Ved are part of the Intellectual Property Rights practice at K Singhania & Co., Mumbai.

Please note that the views shared are personal and do not constitute legal advice.

[1] Reuters, 2 July 2012: “Apple pays $60 million to settle China iPad trademark dispute

[2] 2024 SCC OnLine Bom 2786

[3] CS(COMM) – 600/2021

[4] 2024 SCC OnLine Bom 2786